It was the evening of the fourth of May, and the old shepherd Andrej was looking forward to an evening at the village inn. It was still cold here in the Carpathians, and a warm hearthfire, a jug of wine and a dish of bryndzové halušky, made from the milk of Andrej's own ewes (Andrej bartered milk, wool and rarely mutton with various innkeepers and merchants throughout the area) would be welcome. Andrej's rheumatism was flaring up, and he welcomed the opportunity to sleep in a bed instead of the ground under the stars.

Especially tonight, the fourth of May.

As Andrej herded his sheep into one of the pens near the edge of the village, he counted them, using his rosary beads to keep track of how many had entered. Since it was spring there were numerous lambs to keep track of. He finished his tally, frowning to himself. Eighty-four, he thought to himself. There should be eighty-five. He started his count again. He knew exactly how many rams, ewes and lambs he owned. At the end of the recount, he still came up one short. A lamb had gone missing.

He pondered, thinking of the road he had taken to the village. Several miles back the road skirted a forest, and some of the sheep had been out of his sight around a curve for part of the journey past it. He would have to go back and find the lamb. It was about an hour before sunset, and he probably had time, if the lamb hadn't strayed too far.

It was, however, the fourth of May. People here in the mountains would not willingly go out after dark on the fourth of May. Some would call them superstitious - - they themselves did not, referring to it instead as piety. You didn't go outside on the eve of St. George's Day, nor on other days throughout the year - - the eve of All Hallows or the feast day of St. Walpurga, which had passed several days before. Andrej had stayed the night in another village some twenty miles back on that day.

He called to Štefan, the peasant charged with watching over the animal pens, and told him that he was going in search of a lamb, back toward the forest. Štefan glanced at the sun, now westering, casting long shadows, and said, "You know what evening this is, yes?" Andrej nodded. Štefan went into his hut, returned with several heads of garlic. "Go with God, Andrej. Try to be back before dusk, yes?" Andrej nodded again, taking the garlic and stuffing them into a pocket. He also took out his rosary and draped it around his neck, outside of his lambskin tunic, pausing to kiss the crucifix reverently. Taking up his valaška he set off down the road, Štefan watching silently until the cold drove him into his hut.

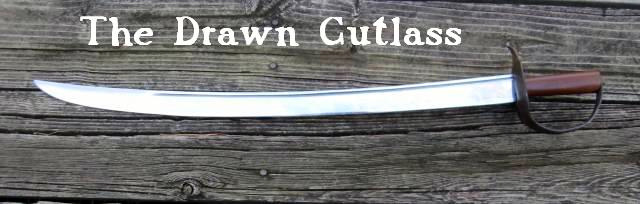

It had been a clear, sunny day, but with not much warmth in the air, because of the elevation here in the mountain foothills. Now, with the sun nearly on the horizon and obscured here and there by trees, evening brought a chill. The steel axehead of Andrej's valaška was cold in his hand, even through the fingerless gloves that he wore. The valaška was the ethnic weapon of the Slovak: a cane-length staff with an axehead at one end and a spike at the other end to assist in walking. Andrej's valaška had an axe blade on one side and a hammering head on the other. Some valaškas, instead of a hammer, had a spike for digging in the ground. Andrej preferred the hammering head; it was useful when he made camp in the evenings. Some effete town Slovaks carried valaška-like objects with ornamental brass or wooden heads, useless for any serious work, and he had heard stories that in the largest cities Slovaks were forbidden by law to carry a valaška at all. He snorted. The proper Slovak response to such a demand is to bash the stupid whoreson over the head with it!

He had walked about two miles along the road, seeing no sign of the lamb. He was now in the forested area where he suspected that the little animal went astray. He heard no howls that would indicate wolves in the area, but foxes abound in the wilderness and happily eat lamb when the opportunity offers. The sun was down now behind the horizon, but the glow of evening was still bright enough to see by. Andrej's breath steamed a bit as he walked.

Suddenly, off the road in the forest he heard the bleating of a lamb, hungry and calling for its mother. Andrej muttered "I'm coming!" under his breath, and plunged into the forest. As he ventured further he paused to leave blaze-marks on trees he passed, not wishing to become lost in the darkness. The bleating of the lamb continued, now a little more faintly, as if the lamb was moving further into the forest. Andrej followed, hoping he could get the lamb and be back on the road before it was fully dark; it was, after all, the fourth of May. That thought caused him to shiver, as if someone had stepped on his grave, as the old saying goes. He began murmuring prayers under his breath as he strode on, the spike of his valaška sinking into the forest floor and helping him to recover when he stumbled. He said a Pater Noster, then an Ave Maria, the last line of which he hoped wasn't a premonition: now and at the hour of our death. He next said a Gloria Patri and this reassured him, so he repeated it as he walked, listening for the lamb and striking passing trees with the axehead of his valaška, scoring the bark off and exposing the white wood underneath, a blaze to help him find his way back to the road.

The bleating of the lamb then became frenzied, and much closer; and, peering through the gloom of the trees, he saw the lamb ahead of him, with a figure in white crouching over it. A large oak tree overspread the ground beside the lamb and the crouching figure. Andrej plunged forward with a cry. The figure in white turned sharply, hearing the noise; a white face shown pale, with red eyes and the heavy mustachios of a Slovak: hatless, the lambskin tunic filthy, the wide belt stained as if with water damage; the breeks torn as by thorns; no shoes or stockings on the dirty feet. Andrej felt a chill run down his spine. Upir, he thought to himself. Vampire.

"Vade retro, Satana!" shouted Andrej, his voice trembling. The words recalled the rest of the incantation against evil things, and Andrej shouted them at the upir:

Crux sancta mihi lux,

Non draco mihi dux,

Vade retro, Satana!

Numquam suade mihi vana;

Sunt mala quae libas.

Ipse venena bibas!

(Let the Holy Cross be my light,

Let not the Dragon be my guide,

Step back, Satan!

Never tempt me with vain things;

What you offer me is evil.

Drink the poison yourself!)

The upir shrieked, as if the words burned it; then, with arms outstretched and claws grasping, it rushed at Andrej. Andrej, stepping back himself, caught his ankle in a root and fell backwards, grasping convulsively at his valaška as he did so, and as the upir fell upon him, he raised it so the spike projected outward. The upir's spring met the spike and it pierced his chest, transfixing his heart. Screaming, the upir clawed at Andrej, who held tightly to the valaška so that the upir would not pull it out. As the upir struggled with Andrej its claws touched Anrej's rosary beads, which burned his undead flesh.

Andrej finally managed to kick and punch himself loose from the upir, not without receiving some scratches from the creature's claws on his arms and face. Andrej rolled onto his hands and knees beside the upir, which was convulsing on the ground beside him, the valaška still embedded in its chest. Andrej got shakily to his feet and grasped the valaška by its head, using it to turn the upir onto its back. He leaned his weight on the valaška, driving it deeper into the monster's body and finally through it, fastening the vampire to the ground. The upir screamed and screamed, its long fangs cutting its lips, its Slovak tunic a blanket of black heart's blood. Andrej held it there, pinioned, while its struggles became feebler, and its screams died down to inarticulate hisses. Finally, it was still. The lamb continued its bleating a few yards away.

It was now fully dark. Andrej stood shakily on his feet, panting. I am getting too old for this, he thought to himself. He crossed himself and said a quick Gloria Patri, then a sort of mini-Litany that he made up on the spot, thanking the Father, Jesus the Son, the Holy Ghost, the Virgin and St. Andrew (his patron) for preserving his life. Nearby the lamb still bleated.

Andrej looked at the dead upir, with Andrej's valaška still sticking out of its chest. Andrej knew that, to be sure of a vampire's destruction, that it was advisable to cut off the head. He thought for a minute or so, then figured a solution. He went over to the dead upir and grasped the axehead of the valaška, then shook it slightly, making sure the undead was truly dead. It remained still. Andrej, grasping the valaška, turned the dead upir onto its side; then, placing his booted foot on the shaft of the valaška halfway down its length, he hauled up sharply on the head, breaking it off so that the lower half was still embedded in the upir's dead body, while the upper half now gave him a stubby hatchet. He used this to chop off the upir's head; it took about a dozen strokes, and revolted Andrej so much that he grunted with each swing: Ugh! Ugh! Ugh! Finally the head separated from the body, which at that point sagged and seemed to slacken. Andrej, remembering the garlic that Štefan had given him, pulled it out of his pocket, and stuffed the garlic into the upir's dead mouth, using the stub of the valaška's handle to push it in. The dead upir's eyes stared unseeing. The lamb continued its pitiable bleating.

Andrej looked around. It was fully dark and time to leave. No use tempting Satan further. He slid the remains of his valaška under his wide, nail-studded Slovak belt and went over to the lamb. Picking it up, he looked around one last time, then began his return to the road, looking for the blazes he had left on the trees. He found them, and soon was back to the road. He began his trip back to the village, the lamb in his arms.

Not long before he left the forested area, off to the right, he suddenly saw a blue light out of the corner of his eye, just off the road, near the beginning of the trees. Remembering the old legends, he quickly put the lamb down and ran over to the ground where a blue flame danced. He took the remains of his valaška from his belt, and stuck it into the ground where the flame showed; then he backed away to the road, squinting to make sure that the shiny axe-head was visible from the road. It was. He again picked up the lamb, and walked the miles back to the village. When he arrived, of course the superstitious peasants would not let him into the inn; even Štefan at the animal pens had his door bolted firmly shut and would not answer his calls. Andrej, resigned, placed the lamb into the animal pen, watching until it found its mother and began suckling, then made his way over to the church, which he knew would be open: churches in Slovakia remain open the year around; evil things will not enter, and honest men fear to steal from the House of God. Andrej entered the church and, asking forgiveness from God, drank some of the Holy Water, and used more of it to clean the scratches that the upir left on his face and arms. The water felt clean and wholesome on his skin. After his ablutions he went to the communion rail and knelt, and thanked God for his deliverance. A devout man, he said the Publican's Prayer: Lord, have mercy on me, a poor sinner. He said this again and again, hoping that God heard. Finally, he crossed himself, and crept into a corner to sleep, his stomach grumbling at a missed supper, but he sternly told his stomach to be quiet.

He slept through until dawn the next morning, when he was awakened by the priest, who came to say his daily Mass. Andrej asked the priest to hear his confession, which shocked and horrified the old man, then stayed for Mass; he took Communion, again thanking God for His mercy.

After Mass he went to the inn for a proper bath and a huge breakfast. The innkeeper apologized for not admitting him the night before; Andrej shrugged it off, knowing the custom of the country as well as any man. He'd have done the same himself, if he had a house of his own. After breakfast he made his way to the animal pens and talked to Štefan of the previous night's events; not going into much detail. He borrowed a spade and a sack from Štefan and, promising to be back in a couple of hours, strode off down the road yet again.

He soon found himself in the forest, next to the huge oak tree where the body of the upir still remained. Using the spade he quickly dug two shallow graves; into one he dragged the upir's dead body; into the other he placed the head. He covered them over with dirt and leaves, said a quick prayer for the upir's soul, and departed.

He made his way back toward the village; along the way he looked for his valaška along the side of the road, where he had spiked it into the ground; eventually he found it. Pulling it out of the ground, he dug in that spot with the spade; about a foot down the spade struck something which scraped at the edge of the blade. Stooping down to the hole he scraped carefully until he revealed a terra-cotta pot, such as one might cook food in. Dragging it out of the hole he laid it on its side, looked at it carefully for a few moments, then struck it with the hammering head of his valaška, shattering it. Hundreds of coins spilled out; most of them the black of old silver, but more than a few shiny golden coins, as well. Picking one of these up he saw that it was Roman, and the emperor shown on the face was Marcus Aurelius. Most of the coins in the pile were Roman, as well, but some were from the Germanic tribes of the period, or so he guessed. He gathered all of them into the bag and, thanking God for his good fortune, returned to the village.

Epilogue: Slovak By the Sea

Andrej gifted a tenth of his hoard to the priest at the village church, to be used for the good of the community. He gifted Štefan his herd of sheep, purchased a horse, and vanished. He made his way to the sea, which he had never seen: the Adriatic, where he made his way to one of the islands off the Balkan coast, where he had a stone cottage built and where he lived in sunny quiet the rest of his days. He dressed as the other locals did, save for his fierce Slovak mustache, and the strange axe-headed cane he always carried. Occasionally after drinking too much wine he'd hint about his adventurous past, and pat the cane affectionately; you never know, he'd say, when you'll need a good valaška by your side!

© 23 March 2013 by Robert G. Evans. All Rights Reserved.

Saturday, March 23, 2013

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

7 comments:

Good short story loved it,wish i could write like that well done.AJD

Bravo.

Excellent. I very much enjoyed the read. You should write of his youth, and the customs of his era.

Liked it.

BZ

I like it.

@Ajdshootist: Thanks!

@Murphy's Law: Thanks!

@Stephen: That'd take more research than I'm willing to put in, frankly.

@KurtP: Thanks!

@DontWantTo: Thanks, and thanks for visiting!

VERY well done! Good job, sir.

Post a Comment